“I want to suggest that one of the worries about robots that you hear about a lot—and it’s a legitimate worry—is that robots are going to take our jobs.”

Kevin Kelly, sat comfortably on a common stool, drops this quasi-dystopian bomb on an inspired, tech-savvy crowd at a SXSW lecture. You can almost feel the tech professionals and geek culture enthusiasts squirming at his feet. Older in age and softened by the confidence of his wisdom, the Wired Magazine co-founder acknowledges the likely future calmly, but with a furrowed brow. You know instantly that he’s about to challenge mainstream reactions.

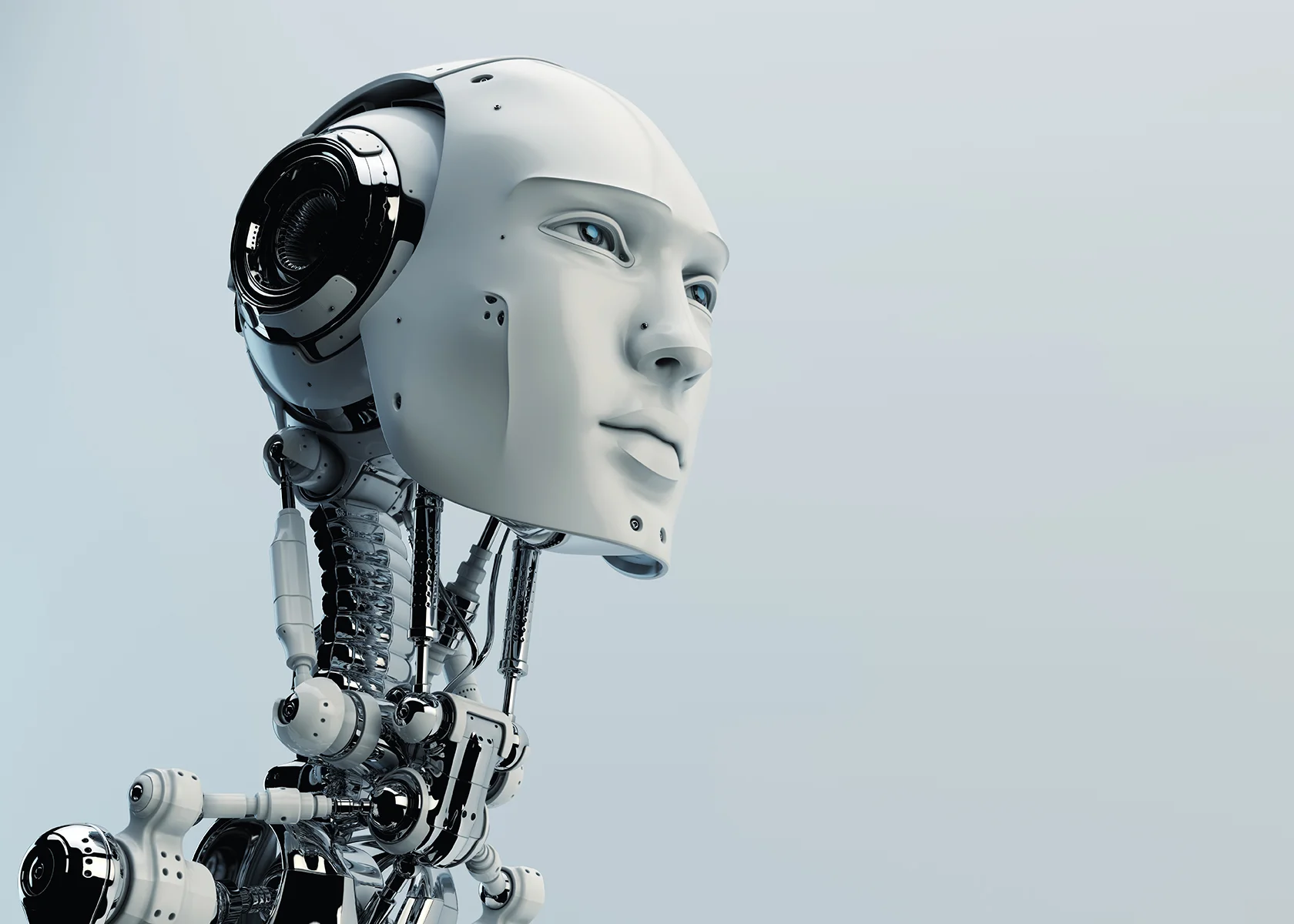

The tech prophet admits that the quickening growth of artificial intelligence is one of the “12 Inevitable Tech Forces” that title his highly anticipated new book. More and more is it seemingly impossible to refute—a signifier of a shifting zeitgeist that today can hardly be challenged. We can look at Boston Dynamics, who are creating androids so human-like in movement that it’s almost disturbing. Our hairs stand on end when you watch the Atlas model get knocked forwards off its feet, consciously come to all fours, and slowly stand back up. More confounding still is the spectacle of the four-legged Spot model stumbling sideways like a startled young deer, successfully staying on its feet with an animalistic, panicked response. Kelly also explains that other models, who can “learn” from colleagues, have a steel foot in the door. They harness the technology of recognizing visual patterns, and are able to watch a human perform a simple performance and repeat it on their own, leapfrogging pre-programmed code that relate to individual tasks.

Still, Kelly stands (or sits, rather) in defiance, and points out that such machines of basic intelligence can move in only to occupy spheres of “efficiency.” In considering the nucleus of contemporary business being cemented in just that (consider our desperation for fast wifi alone), how does a brand get ahead when ubiquitous, salary-independent tech makes everyone move at the same speed?

As Kelly calmly and prophetically explains, the advantages for brands simply shift to new areas. Differentiation, with human efforts being booted out of old-school, industrial efficiency, will become more dependent on the things humans could only ever do. That means creative solutions, emotional empathy, artistic innovation, and highly tailored content.

Take an example from my long-beloved arena of healthcare—a hypothetical hospital where the near-perfect accuracy of A.I. is responsible for anything from routine surgery to changing the sheets, and patient transfer to dosage adjustments. Doctors and nurses would, as expected, become more focused on patient relations, emotional intelligence, and fostering mental health—aligning with the actual experience of a hospital, instead of just running it. In the responsibilities of admin pushed to the side, staff would have much more time—and therefore more responsibility—to treat each patient in time, with care, and as an individual. These skills of hearing and reading, reserved for humans, are a hallmark for good healthcare.

Of course, the implications for PR/Comms professionals beyond the white walls are simply immense. As it has already happened to American agriculture, per Kelly’s reminder, we know that a rise in tech automation means a shift in human focus from efficiency to personality, and cold convenience to emotional engagement. Content and user customization will almost surely far transcend even its current importance, and direct human-to-human relations with consumers will be the key to staying personal in an increasingly binary world.

It’s brilliantly ironic to think that in freely adopting A.I., business could be more humanized than ever.